Cab Calloway has always creeped me out. His voice is otherworldly and his dancing is insane. Fleischer-animated Calloway is ur-Calloway. Happy Halloween!

Tuesday, October 31, 2017

Then Give Me Six Crap-Shootin' Pallbearers

Cab Calloway sings "St. James' Infirmary" in Betty Boop's "Snow White," 1933:

Cab Calloway has always creeped me out. His voice is otherworldly and his dancing is insane. Fleischer-animated Calloway is ur-Calloway. Happy Halloween!

Cab Calloway has always creeped me out. His voice is otherworldly and his dancing is insane. Fleischer-animated Calloway is ur-Calloway. Happy Halloween!

Sunday, October 29, 2017

Night Life (1971)

Following from the last Night Life, we have another mention of Ahmad Jamal. This time it's a total slam: "Ahmad Jamal, of the flexible fingers and occasionally interesting ideas." Wow.

I'm not familiar with what Jamal was doing music-wise in October 1971, but I do own The Awakening, a record Jamal recorded in February 1970 for Impulse! Records with Jamil Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums. I've found Jamal's post-classic trio 1960s output to be less than amazing, but The Awakening is true to its title.

Jamal was always the controlling voice in the trio, so any bassist and drummer needed to find ways to make themselves heard. Israel Crosby did this through incredibly creative basslines that put the bass to the forefront in the trio setting as much as Scott LaFaro's work with Bill Evans (in a much more democratic trio) was doing in the same years; drummer Vernel Fournier made himself heard almost through negative sound, establishing himself as the master of deceptive simplicity at the drums, hitting a groove and holding it like a rhythmic pedal point.

The trio with Nasser and Gant took some time to really hit its stride, which I think they did with The Awakening. Both bassist and drummer had done extensive work with lots of incredible musicians prior to joining Jamal, and they both bring real force to the Jamal sound. Jamal himself is obviously working with new vocabulary, blending his classic approach, with an active right hand and thick left-hand chords, with very Hancockian touches. The overall sound is darker and meatier than what he was playing ten years earlier. The set list is great, too - "Stolen Moments" and "Dolphin Dance" are highlights.

All of this is to say that while I don't know what Jamal was up to a year and a half later, I find it hard to believe he'd totally stagnated in that time. I don't know what the New Yorker's problem is, but my feeling is that their dismissal of Jamal was undeserved.

Given the choice, though, I wouldn't be going to the Village Gate to catch Jamal (or to the Vanguard, recipient of another burn). My money for show of the week is on the doings at Slugs'. The club would close soon after Lee Morgan was murdered there in 1972, but in '71 the place was happening, with Andrew Hill, Herbie Hancock, James Moody and Eddie Jefferson all appearing there. Damn! Hancock came out with Mwandishi in '71, so my guess is the group from that record (including Jabali/Billy Hart) is the sextet referred to in the listing. Andrew Hill wasn't releasing jack in 1971, but some tracks from '70 got issued by Blue Note in 1975, the the same year Hill released five records on East Wind and Freedom labels; he really got things going again in the mid-1970s, so it would have been cool to hear what he was up to during his absence from the studio.

Overall, though, you can really see how there was a resurgence of clubs as we get into the late 1970s and early 1980s. Even in the late 1980s, you saw swing-era and bebop guys playing all over the city, but they're nowhere to be found this week in 1971.

*

From The New Yorker, October 30th, 1971:

Friday, October 27, 2017

Tuesday, October 24, 2017

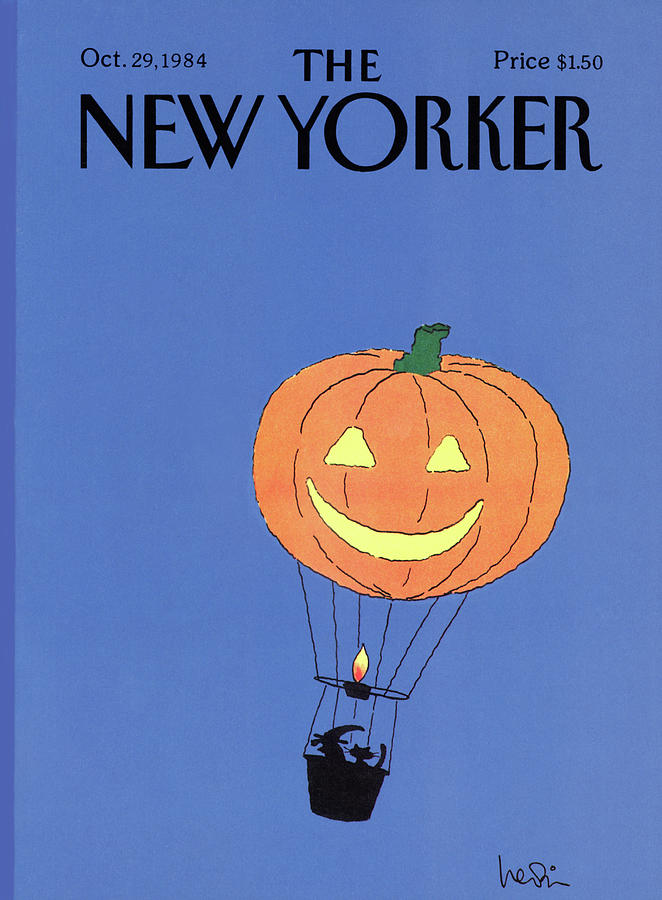

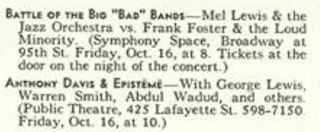

Night Life (1984)

A few interesting things in the New Yorker jazz listings for October 29th, 1984.

First, Billy Eckstine - appearing at the Blue Note - was only fifty-one. He died after a stroke and a heart attack in 1992 and 1993, when he was seventy-eight years old. Miles Davis, who always cherished his time in Eckstine's famous big band in the 1940s, had died in 1991, at only sixty-five. Because so many of the legends of jazz had highly publicized careers in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, it's easy to think of them as old, old men when they died in the 1990s. But they often were at the age when many other great musicians have still been making vibrant music. Billy Hart is seventy-six; next year, Joe Lovano will be sixty-five.

Second, Gil Evans was apparently playing "Charlie Parker tunes on top of a heavy rock beat" at Lush Life. There are a few videos on YouTube of Evans (whose band included Howard Johnson on tuba) playing in Japan with Jaco Pastorius in 1984. As far as seamless transitions into the world of pop and rock go, I'd say this isn't exactly in my top ten:

Nevertheless, it's a good example of what can be learned from these jazz listings: they present the reality of the music scene, not necessarily the highlights.

Third, I think it's interesting that Ahmad Jamal, playing at the Village Vanguard, is even in 1984 described as "controversial," an allusion to accusations of cocktail-pianism leveled at him early in his career (Martin Williams didn't like him). Perhaps this is just the pre-Wynton Marsalis world (although Wynton is also appearing at the Vanguard - but I mean pre-Wynton's educational initiatives), before the narrative of jazz history was codified. Jamal is now naturally slotted as a minor player before Miles's first Great Quintet with Coltrane for his influence on Miles's tune choices and and piano preferences; his actual music is rarely discussed in overviews of the history. Still, it seems weird to still be calling Jamal controversial a quarter-century after "Poinciana."

Actually, The New York Times noted Jamal's run at the Vanguard on October 29th as well. The paper wrote that

Ahmad Jamal's primary distinction as a jazz pianist has been in his use of dynamics and coloristic effects. He established this musical identity almost 30 years ago when, leading a trio that included the superb bassist, Israel Crosby, and the drummer Vernel Fournier, he made subtle and sometimes dramatic use of silence and of Mr. Crosby's exquisite touch on bass.

Jamal's last record had come out in 1982 - information about American Classical Music isn't readily available. His next record came out in 1985; Scott Yanow calls it "not essential."

*

From The New Yorker, October 29th, 1984:

Thursday, October 19, 2017

Saul Steinberg (1967)

"I start sometimes making a hand, holding a pen and making a drawing. This gives me time to think of what drawing this pen is going to do. I also want these moments to lose the responsibility of the drawing. It's not I who makes this drawing, it's that hand I drew who makes it.... But this way I have a certain freedom, a certain lack of responsibility."

I hadn't seen this 1967 interview with Saul Steinberg by Adrienne Clarkson. Steinberg is a fascinating thinker about how and why art works; his memoir, Reflections and Shadows (written with Aldo Buzzi), is a treasure trove of insights. The section where Steinberg discusses surrealist painter Magritte has stuck with me. "I liked some of his things," Steinberg says in the book, "but in general I thought he worked too hard at painting just to explain a joke" (Steinberg 57).

Deirdre Blair's 2012 biography of Steinberg notes that, "When Sidney Janis owed [Steinberg] $400, Steinberg asked for a Magritte instead." I don't have Blair's book in front of me now, so I can't check her sources, but I bet she got this tidbit from Reflections and Shadows. There, Steinberg says that "I have one of the earlier Magrittes, from 1926, one of his best, I think, and well painted with that famous patience.... I bought it from my dealer, Sidney Janis, who owed me four hundred dollars." He continues:

It's a double portrait of André Breton: two profiles, one saying "Le piano" and the other answering "La violette." The speech balloons coming out of the two mouths are of a dense and opaque salmon-violet color, and are fairly elongated in shape. Maybe in choosing this color, Magritte meant to show a continuation of the two tongues. It's probably a joke on the comic strips. (58)Steinberg's tone implies that he doesn't think Magritte's jokes are very funny, however well painted they are!

But the part of Steinberg's Magritte discussion that I've remembered best is his description of "Empire of Light," a series of three paintings Magritte painted from 1949 to 1954.

Magritte discovered the three sources of light (and maybe a few more). In a painting of which he did several variants, you see the sky illuminated by the last reflections of the sunset, while the other elements of the landscape, a tree, a house, are dark silhouettes against the sky. On the street there's a streetlamp, already on, which illuminates part of the street and part of the house. In the house the electric light is on, illuminating the interior and shining through to the outside: three lights. There's a moon, I think, which is already starting to cast a little light. And I'm almost certain that he also painted a light reflected in a puddle, or maybe one sees a little bit of the sea. (58-59)

|

| Magritte's "Empire of Light" |

Brutal! Steinberg himself drew jokes, and sometimes was even known to play tricks:

So why do I respond so much more to Steinberg's drawings than to Magritte's paintings? Why do I consider Steinberg an artist of vibrant drawings, while I see his point about the somewhat soulless Magritte? There is something about that "lack of responsibility," the "certain freedom" Steinberg allows himself, that makes his jokes seem very relaxed, very natural, very un-self-regarding. When all is said and done, Magritte's jokes don't want to give up being Art. And while Steinberg's work is given "art status," the drawings themselves couldn't care less. I think it has something to do with a certain freedom - a certain lack of responsibility.

Wednesday, October 18, 2017

Night Life (1981)

These moments of reflection, what I see as the hallmark of New Yorker covers, are growing rarer and rarer. It is more possible now for covers to reflect what is happening mere days before the newest edition hits the streets, and covers have gotten more and more topical. I could classify almost all new covers in two categories: first, topical news covers reacting to gun violence, national tragedies, or politics that tap into feelings of sympathy, outrage, sadness, or inspiration; and second, topical humor that uses technology, public figures, or current news items to get a laugh of recognition (many in this category seem to feature hipsters).

I'm not saying that representing current events is wrong, and I think it's important for artists, whether they hang in galleries or create New Yorker covers, to stand up for their principles and draw attention to important issues. But I think that in this world, a world where sadness, outrage, violence and confusion is shouted from every screen every hour of the day and night, it's too bad that we have less quiet moments of peace like the 1981 cover above on our newsstands; less moments when we can step out of the noise and just breathe in some fall air.

*

I've decided to add a little bit of commentary to these Night Life posts. In the traditional narrative of jazz history, the 1970s and early 1980s were a dead period for jazz, when clubs closed and audiences shrank. These New Yorker listings, though, show an incredible diversity of jazz on offer. Anthony Davis, Tommy Flanagan, Teddy Wilson and Sy Oliver, all playing in the same week. The amount of living legends playing regularly in the city during these years is absolutely astounding. Jaki Byard and Major Holley at the Angry Squire - they both appeared on Rahsaan Roland Kirk's Here Comes The Whistleman in 1965. Must have been quite a show.

Friday, October 13, 2017

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)